How to Play Mahjong

Mahjong, also spelled majiang or mah jongg, as it is played around the world today, is not the ancient Chinese pastime you might think it to be.

Stories are often told of a lonely Tang Dynasty princess who invented the game to ward off boredom more than twelve hundred years ago. Many say Confucius himself enjoyed the game as Ma-chur, and there are even a few who claim the game entertained Noah and his family on the Ark.

In truth, however, the current game was invented only about 150 years ago. In 1846, the rules of a set-forming card game—Ma Tiao, which was similar to Gin Rummy and very popular in Shanghai—were applied to a ceramic tile game by a clever imperial servant named Chen Yu-Men.

Decades later, when China became a Republic in 1912, the game took off as a welcome diversion from troubled times. It was called “mahjong,” which means “hemp bird” or “sparrow,” because getting the winning piece is as difficult as catching the Chinese bird of cleverness.

Mahjong Rules

From China, Mahjong was exported worldwide, gaining unprecedented popularity in Europe, the Americas and elsewhere in Asia in the 1920s.

Perhaps because the original rules of the game were rather difficult to learn, each culture made modifications, so that today the version played in Japan called “Riichi Mahjong” is quite different from the “All-American Mah Jongg” enjoyed in the United States.

Internationally, however, the original Chinese form is still considered the gold standard. The basic game of Mahjong is played by four persons and, much like poker, is enjoyed not only as a social activity and a form of family recreation, but also for gambling and serious competition.

The game is played with a set of tiles based on Chinese characters and symbols, although some regional variations use a different number of tiles.

Mahjong Tiles

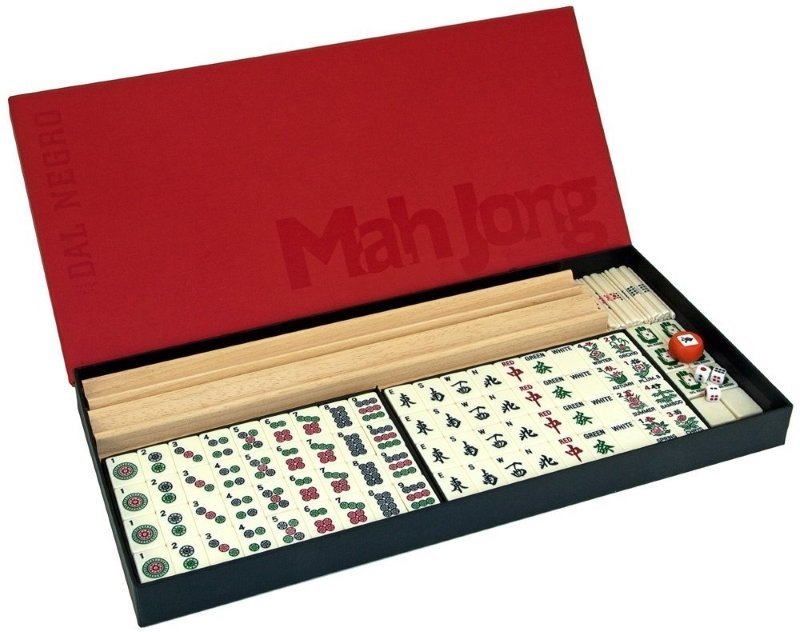

Although there are many variations in the way Mahjong is played and scored, the basic pieces used in the game are quite similar all over the world. A standard Mahjong set will contain 136 playing pieces called “tiles,” a pair of dice, a number of stick-like counters used to keep track of the score, and eight “bonus tiles” not used in play.

Optional pieces include racks to hold the tiles for four separate hands, a “Prevailing Wind” marker to indicate the round/deal, and “wind discs” for identifying players’ positions. There may also be several blank tiles included, which can be used to replace any missing pieces.

If you think of the Mahjong tiles like a standard deck of cards, then there are three basic suits: bamboos, dots and characters. Each suit contains four sets of nine tiles, for 36 tiles apiece and 108 in total. Western-style Mahjong sets may have the numbers 1~9 printed on the suit tiles to make it easier to identify their values.

The Bamboo Suit is always easy to identify. The face of each tile bears a number of bamboo segments corresponding to its value, with the exception of the One of Bamboos. This piece is usually depicted by a lone bird—called Pe-Ling—which may be a song bird, peacock, pheasant or sparrow.

The Dots Suits—sometimes called “circles” or “balls”—is also easy to pick out. Each tile features a number of dots representing its value, again one through nine.

The third suit, Characters, can be a bit confusing for those unfamiliar with Chinese ideographs. The upper half of each tile shows a number, one through nine, written in blue Chinese script.

The bottom half portrays the character for “ten thousand” in red, so the tiles actually represent the numbers ten thousand through ninety thousand. For this reason, the Characters Suit is sometimes referred to as the “Grands.”

Besides the 108 suit tiles, there are 28 Honor Tiles. These include four sets of three Dragon Tiles and four sets of four Wind Tiles or Directional Tiles. The characters for the Dragons, sometimes called Cardinal Tiles, can be identified by their colours.

The Red Dragon, Chung (meaning middle), is painted in red. The Green Dragon, Fa (growth), is in green. The remaining Dragon Tile, Po (blank), has no writing on it at all and is often called the White Dragon.

The Wind Tiles, as might be expected, bear the Chinese ideographs for East, South, West and North. In Western sets, these may be marked with the letters E, S, W, and N.

Note that the four directions always begin with the East, where the sun rises, not the North, where the compass points—an interesting distinction between Oriental and Occidental views of the world.

The optional eight Bonus Tiles usually represent Flowers—Plum, Orchid, Chrysanthemum, and Bamboo—and the Seasons—Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. They may be numbered, 1~4, for each set, and can be very stylized in their designs.

In some Chinese sets, they may even depict the eight apostles of Lao Tse. Quite often they are the most beautifully illustrated of all the tiles in a set, although they are not necessary to play the game.

Getting Ready to Play Mahjong

Apart from having a Mahjong set, you need four players for a game of Mahjong. Some versions have been invented for two or three players, and online you may encounter a popular program known as Mahjong Solitaire for solo play. But the real game, much like Contract Bridge, can only be enjoyed by a foursome.

Seating is at a square Mahjong table, typically covered with green or blue felt similar to that seen on poker tables. The table may also have recessed trays along the edges for collecting tiles, or at least a lipped edge so that tiles do not easily fall onto the floor during shuffling.

Before beginning, the players should agree on the stakes. This is usually a certain amount per point with a limit on the maximum number of points that a single player may have to pay to another during any given round.

As players get seated at the table, each is given an identifying compass direction. The optional “wind discs” can be drawn by lot for this purpose, or the Wind Tiles can be used. Dice may be thrown, too.

Players take their seats in order, E-S-W-N counterclockwise, beginning from the East, who will be the first dealer. The “Prevailing Wind” marker, if used, is initially set to East as well.

If you have never shuffled Mahjong tiles, you are in for a treat. The 136 playing pieces are placed face down on the surface of the table, then all four players reach in and begin mixing them without allowing any to turn over.

The distinctive clatter of Mahjong tiles being shuffled is what draws many young players to the game in the first place. The sound is as unforgettable as it is unmistakable.

Once the tiles have been thoroughly mixed, the players begin building a square structure known as the “Wall.” Each side of the Wall is seventeen tiles long and two tiles high.

The tiles are stacked in pairs atop each other so that their faces are down with the length of each tile perpendicular to the long axis of the section of the Wall it is in. All 136 tiles will be used to form the Wall.

Next, East will roll the two dice and count counterclockwise around the table to determine which player will “Break the Wall.” For example, if a total of two is rolled, West will break the wall. If three is the total, then North will create the break, etc.

Whoever is designated to break the wall must do so by rolling the dice again and then counting that many tiles clockwise from the right end of his/her section of Wall.

The break is created by forming a gap in the Wall immediately to the left of the tiles counted. In other words, if a total of seven were rolled on the dice, the gap would be formed between the seventh and eighth stacked pairs of ties.

Now, the East player takes four tiles from the wall to place in his/her hand. The four tiles must be the two pairs stacked clockwise from the break. East places the tiles in a rack or stands them in a line so that the faces may not be seen by the other players.

Then, the South player takes four tiles and begins forming a hand, and each player continues to do so in turn until all have drawn a dozen tiles.

The “deal” is completed by East taking two last tiles, one of them being the next tile from the edge of the Wall, and the other being the top tile two over. The other players, in turn, take one tile each, which will leave a single tile facing down from under the last tile that East took.

This tile will be the first one drawn when the game actually begins. All players now have a hand of thirteen tiles, save East, who will discard one when play begins.

In some variants of the game, particularly those in which the Bonus Tiles are used, a “Dead Wall” is formed of the last fourteen tiles on the far end of the Wall.

To do so, the seventh pair of tiles from the far end of the Wall must be taken up. One of these loose tiles is placed face down on top of the last tile on the Dead Wall and the other goes on top of the third-to-last pair.

Mahjong – Forming Melds – Chow, Pung and Kong

The object of Mahjong is to be the first player to collect a set of fourteen tiles grouped into four “melds” of three tiles each plus a matched pair. The melds typically take either of two basic forms—a Pung or a Chow.

To use familiar poker terminology, a Pung is “three of a kind,” which is formed by any three identical tiles. Similarly, a Chow can be thought of as a “straight flush,” which must be formed by three tiles of consecutive numbers in a single suit. Due to this suit requirement, Winds and Dragons cannot be used to form Chows.

When it comes to scoring, Chows have no value. However, they are used as basic building blocks to form and complete hands. If you create a Chow by pulling a tile from the Wall during your turn or by picking up a discard from the player to your left, you announce “Chow.”

You then meld it by displaying the two tiles from your hand in front of you face up and adding the third tile to them for all to see.

Pungs, on the other hand, factor into scoring. You create a melded Pung in the same way you create a melded Chow by exposing two of your tiles and adding a discarded third tile face up. But unlike the melded Chow, you can claim a melded Pung with any player’s discard. It does not have to be your turn.

Another difference between Pungs and Chows occurs when you create a Pung by drawing a tile from the Wall. You do not have to expose it. This “concealed Pung” can remain hidden in your hand, where it is worth twice as much as a melded Pung.

One other reason to keep a Pung concealed is the possibility of a special meld called a Kong, or “four of a kind.” It is made up of four identical tiles and adds scoring value to a winning hand.

Kongs are melded by adding a discarded tile or a tile from the Wall to a concealed Pung and exposing the four tiles. Just as when calling a Pung, you can claim a melded Kong on a discarded tile from any player; it does not have to be your turn.

To display a Kong formed by claiming a discard, place all four tiles face up next to each other. To display a Kong formed with a tile taken from the Wall, show the four tiles to the other players, and then place them on the table with the two outer tiles face up and the two inner tiles face down. This indicates that it is worth additional scoring value.

Because forming a Kong leaves the hand short a tile, the declarer draws one of the two loose tiles from atop the Dead Wall. However, this extra tile may only be claimed when the Kong is declared, so concealing a Kong when drawing from the Wall is uncommon, unless done as a purely tactical manoeuvre.

In most versions of Mahjong, there must always be 13~14 tiles in the Dead Wall. For that reason, the removal of loose tiles for Kongs may require that tiles from the end of the “live” Wall be used to replace any loose ones that are taken. Such replacement is often affected after both loose tiles have been removed, or may be done as each tile is taken.

Mahjong Basic Play

With the Wall erected and the tiles dealt out, the four players each sort their hands, looking for potential melds. The game of Mahjong begins with East, the dealer, who has drawn 14 tiles and thus has one more than the other players.

If East somehow has obtained four melds and a pair right from the start, it is a natural “Hand from Heaven.” East instantly wins the hand, scores the maximum number of points, and retains the deal for the next hand. As you might imagine, this is an extremely rare occurrence.

In most cases, East will not have a pat hand and will instead have to discard one of the original fourteen tiles. The discard must be placed face up in the “Courtyard” at the center of the table, surrounded by the Wall.

Only the next player in order, South, can use the discard to form a Chow, but any player may claim it for a Pung or a Kong. Moreover, a claim for a Pung or a Kong takes precedence over a claim for a Chow.

If a Pung is called by claiming a discarded tile, it becomes the declaring player’s turn, regardless of whose turn it would normally have been next. If a Kong is called using a discard, play continues in order after the declarer has drawn a tile from the Dead Wall to fill the depleted hand.

In many cases, no one wants to claim the discarded tile, and it will remain out of play for the rest of the hand. Instead, the next player whose turn it is, South, draws a tile from the front end of the Wall and adds it to his/her hand, exposing the meld if it forms a Chow or Kong and concealing it if it forms a Pung. The player then discards a tile, and play continues counterclockwise.

When discarding a tile, it is proper Mahjong etiquette to call out the name of the piece being placed in the Courtyard—“Two Bamboo,” “Red Dragon,” East Wind,” etc. When picking up a discarded tile, it is also appropriate to announce the meld being formed—“Chow,” “Pung” or “Kong,” or “Mahjong” upon completing a hand.

During play, it is possible to upgrade an exposed Pung to a Kong by drawing a tile from the Wall. If this occurs, the drawing player must immediately declare the upgrade, add the drawn tile to the melded Pung, and draw a loose tile from the Dead Wall before discarding. An exposed Pung may not be upgraded by using a tile discarded by another player.

The game continues in this way, with players drawing tiles from the Wall or claiming discarded tiles until one of them is almost ready to complete a winning hand with four melded sets and a pair. A hand that is one tile short of completion is called a “Waiting Hand.”

The fourteenth and final tile must complete one of three basic elements—a Chow, a Pung or a Pair—and it can be drawn from the Wall or claimed from any player’s discard. A claim to win the game takes precedence over all other claims.

Please note that the Pair can be formed at any time from the original tiles dealt, or by drawing a tile from the Wall. It may not, however, be created by claiming a discarded tile, unless it is the last tile needed to complete the hand.

Once a player has a “Mahjong” with four melded sets and a pair, the hand is scored, wagers are settled, and the next hand begins with the East wind, or dealer’s position, moving to the next player counterclockwise to the player who was South for the previous hand. However, if East wins the hand, he/she retains the deal and the East position until another player wins a hand.

A single round of Mahjong is completed when all four players have had the opportunity to be the dealer, East, at least one time. Then, the “Prevailing Wind” is switched from East to South, and a new round begins, followed by rounds of West and North as Prevailing Winds, respectively.

Thus, a full game of Mahjong consists of four rounds of “winds,” with each player dealing at least four times.

Mahjong Scoring

Even basic Mahjong scoring can be a bit confusing to beginners. Some combinations of pieces are worth considerably more than others. Some hands have special value, while others are next to worthless. To understand scoring and its affect on playing strategy, you must first know the point values of the various sets.

Points are awarded for various combinations of tiles. As previously noted, a Chow is worth nothing, whether exposed or concealed. Pairs made up of Dragons, the player’s Own Wind or the Prevailing Wind score two points. All other pairs have no value.

Scoring Pungs is a bit more complicated. Among the suit tiles, Pungs made up of “Simples” (tiles numbered 2~8) are worth two points if exposed and four points if concealed. Pungs of Honor Tiles and Terminals (the One or Nine tiles of a suit) score four points if exposed and eight points if concealed.

Exposed Kongs made up of Simples score eight points and those comprised of Honor Tiles or Terminals score 16 points. The values are doubled if the Kong is concealed.

Being the first to declare a Mahjong during a hand earns the winner 20 points. If the winning tiles comes from the Wall or completes a Pair, that is worth two points. And two points can also be earned if the last tile used to complete the hand was the only possible tile that could be drawn to win.

The actual process of scoring a hand moves through three stages, once a Mahjong has been declared: Counting, Doubling and Settling. The first step is for the winning player to add up all of his/her points, based upon the values of the sets in the hand.

For example, if the West player had four Chows and completed the hand by drawing from the Wall a West Wind Tile to form a final Pair, the scoring would be two points for the Own Wind, two points for winning from the Wall, two points for winning by completing the Pair, and 20 points for the Mahjong, for a total of 26 points.

The next step is called Doubling, whereby the points are increased by factors of two. A Double can be earned in a number of ways, and each variant of the game has its own series of Doubles.

The most common, however, are these: a Double for each Pung or Kong of Dragons, Own Wind or Prevailing Wind; a Double for three concealed Pungs; a Double for a Clean Hand (one suit only, plus Honor Tiles); a Double for a Pure Hand (one suit only); and a Double for a hand made up only of Chows or only of Pungs.

In the example given above, West had all Chows. This hand receives a Double and it is now worth 2 x 26 = 52 points. It has no other special values.

In the Settlement phase, each losing player must pay the winner whatever number of points the winning hand is worth. When East wins as dealer, the losers must pay twice the winning score, and East deals again. However, when East loses, East must pay the winner twice as much, and the deal is passed to South, who becomes the East seat for the next deal.

In traditional Mahjong, settling then continues, as the losers add up the Points and Doubles for their own hands, and they then pay each other accordingly. The only difference is that the winner does not participate in this part of the settling and therefore pays nothing.

This makes Mahjong a unique game, in that everyone can receive something for every hand, although what is paid out may be more than what is taken in.

For example, it is quite possible for one of the losing hands to be worth more than the winner’s hand. If West won with 52 points, North finished with 16 points, East ended the hand with 144 points and South had 24 points, then East would actually come up the point leader, despite losing the hand. The settling would go as follows:

West (52 pts) = 52 + 52 + 52 – 0 = +156

North (16 pts) = -52 + 16 + 16 – 144 – 24 = -188

East (144 pts) = -52 + 144 + 144 – 16 – 24 = +196

South (25 pts) = -52 + 24 + 24 – 16 – 144 = -164

As a rule, before starting a game of Mahjong the players will agree among themselves to set a limit on the maximum paid out by one player to any other player on a single hand, typically 2,000 points. Also, to aid in the settling, special counting sticks marked with spots are used, although poker chips can serve the purpose, too.

Mahjong Spreads Worldwide

L.L. Harr was an English aristocrat who lived in Peking in 1919. One night, a Chinese statesman named Li Huang Chang showed Harr a set of ivory tiles that had been artistically painted with pictographs and characters. Li Hung said they were used to play a centuries-old game called “Pe-Ling,” which he invited the Englishman to learn.

Almost immediately, Harr was hooked. Over the next two years, he studied, practiced and mastered the game. Then, in 1921, he boarded a ship bound for Marseilles, taking five sets of the game tiles with him. En route, he convinced a group of whist players to try the Chinese game. By the time they disembarked, everyone aboard the ship was playing nothing but Pe-Ling.

Eventually arriving in London, Harr had only one set of tiles left in his possession. Knowing a business opportunity when he saw one, Harr sent a telegram to friend in China and order eighty more game sets.

Suffice it to say, Harr’s novelty was hit among the upper class in London society. Princess Mary took it up as a pastime, and the Queen gave Prince Charles a set of tiles for his birthday.

Meanwhile, an American oil executive by the name of Joseph Park Babcock had encountered a version of the game with somewhat simpler rules in the gambling dens of Shanghai in 1920.

He brought a set of “Mah Jongg” tiles home to the United States and over the next three years the craze swept the country, replacing Ping Pong as the obsession of the Roaring Twenties. In almost no time at all, Mah Jongg sets became Shanghai’s fifth largest export.

Babcock’s Mah Jongg fad crossed the Atlantic to England, where Pe-Ling players were excited by its simpler rules. They also liked the American tiles, to which identifying numerals had been added. Harr, however, was a purist and fought any changes in the traditional way Pe-Ling was played, causing differing schools of the game to develop.

As you might guess, simplicity eventually won out, and a British version of the game gradually evolved. It allowed for the use of Bonus Tiles, only one Chow per hand, obligatory announcements of Waiting Hands, penalties for mistakes, and the use of Joker Tiles that could be substituted for any needed tile to complete a hand.

In America, even greater innovations took place. A practice called the “Charleston” became common, with players exchanging unwanted tiles at the start of the game.

In the “All-American” version of Mah Jongg, Bonus Tiles and Joker Tiles are used, bringing the total number of tiles in an American set to 152. The Dead Wall was eliminated, additional special hands were created, and new idioms arose, such as the Ding Dong, the Kitty, and the Goulash.

Babcock’s game made its way throughout Europe in the 1920s. In Holland, where the Bonus Tiles were not used, rules were modified slightly to allow winning only with two Doubles or more.

The French added their own modifications, as did the Italians, although the Germans did not take to the game quite as readily—they eventually embraced standard rules with one exception: a winning hand must contain a minimum of 100 points.

Major Mahjong Variations

With such a diversity of playing styles, it is a wonder that Mahjong survived its initial wave of popularity. Indeed, the game fell out of vogue in the United States in the 1930s, replaced by a new pastime—miniature golf—and it did not resurface for nearly four decades.

Even in China, the game’s cultural home, Mahjong was banned when the country went to war with Japan in 1931, and then again in 1966 under edicts from Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which saw it as a corrupt aspect of the “old ways.”

The Japanese, however, embraced the game with a fervor unmatched elsewhere in the world. It was brought to the island nation in 1924, when a former Japanese soldier stationed in China opened a Mahjong school and parlour in Tokyo called the Nan-Nan Club.

Writers, artists, actresses and celebrities quickly took to the game, followed by the entire populace. Within a year, the Japanese Mahjong League was formed to codify local rules and prevent the confusion that cropped up in other countries.

Today, Mahjong is played more in Japan than in any other nation. There are some 22,000 Mahjong clubs across the archipelago, including about 5,000 in Tokyo and another 2,500 in Osaka. The most popular version of the game has been around since the 1950s and it is called “Riichi” (pronounced ree-chee or “reach”), which means “ready.”

In Riichi Mahjong, every player begins the game with 30,000 points or chips. When a player obtains a Waiting Hand, he/she may declare so by placing a 1,000-point marker on the table.

For gambling purposes, 1,000 points is usually worth ¥10 to ¥100. Bonus tiles are not used, the Dead Wall has no loose tiles and is constantly replenished, and no Doubles are required in the winning hand. In Riichi Mahjong, Doubles are called “Fan” and some Fan are special, known as “Yaku.”

There are several other modifications to the standard game that impact scoring. For example, the third to last tile on the Dead Wall is turned face up. This tile is the Dora Indicator.

Whatever tile follows it in order is “Dora” and is worth a Double. For example, if the West Wind Tile is turned up, then the North Wind Tile becomes Dora. Holding a Pung of Dora automatically multiplies the value of a hand by a factor of eight.

When a Kong is revealed at any time turning a hand, the player who exposes it also turns over the tile to the right of the Dora Indicator and reveals an additional Dora. For this reason, players are wise not to reveal a Kong after a player has declared Riichi, else he/she may get additional Doubles.

If the player who declares Riichi wins the hand, he/she gets several special bonuses, not the least of which is an automatic Yaku (special Double) plus the return of the 1,000-point marker used upon declaration. If the declaring player loses, the 1,000 points go to the winner.

To declare Riichi, all of the player’s tiles must be concealed and no changes may be made to the hand after declaration. Upon winning, the player will reveal the hidden tile beneath the Dora Indicator, which is also used as an additional Dora Indicator (the “Ura Dora”), but only for the winning hand.

Other aspects of Riichi Mahjong which are different from standard play include the use of a red-coloured Five Tile in each suit to increase Doubles, a prohibition against going out with a previously discarded tile, penalties for falsely calling a meld, and ending the game when any player has exhausted the initial 30,000 points. Also, there is no settling of the losing hands. Only the winner is paid.

Riichi Mahjong has become quite popular in the United States and on the Internet in recent years. However, the variation that is most commonly played other than the standard version is the game using Bonus Tiles.

When playing with the Bonus Tiles, the four Flower Tiles and four Season Tiles are mixed in with the others during the shuffle. That means there are 144 tiles in total. Instead of seventeen pairs on each side of the Wall, eighteen pairs of tiles are used.

When a Bonus Tile is drawn, it is immediately placed face up in front of the player and replaced by drawing a tile from the Dead Wall, as in the case of forming a Kong.

The Bonus Tiles are only there to add value to the winning hand. Typically, each one exposed is worth four points. If the winning hand contains the player’s Own Bonus Tile, it also receives a Double during scoring.

Mahjong More and More

As you become more familiar with Mahjong play and scoring, you will begin to appreciate the role of Doubles and begin forming your hands to maximise their occurrence.

You will also encounter “special hands” that are worth bonus points, such as a hand contained Pungs and Chows of a single suit or the “Seven Pairs,” which allows winning with only pairs instead the standard single pair plus four melded sets.

Forming a hand that contains your Own Wind or the Prevailing Wind is always a good strategy to obtain Doubles. For that reason, discarding your opponent’s winds may be a bad move, especially in the late stages of a hand. Similarly, Dragon Tiles and Terminals are especially prized for their ability to bring about Doubles, and care must be taken in discarding them, too.

Some players try to complete their hands quickly, looking avoid the need to pay another winner or else to thwart opponents’ efforts to build strong hands. Others play a waiting game, aiming to form the most powerful hand possible.

Your tactics will depend largely on the initial deal, the experience levels of your opponents, and your purpose in playing the game—for recreation, for skill-building, or for money.

Mahjong wagering is technically illegal in most countries, even though authorities tend to turn a blind eye to small stakes games. For this reason, it has rarely become a feature of major casinos, constrained instead to homes and private clubs, even in Japan and Hong Kong.

If you do choose a club to play in, your foursome will be charged a rental fee by the hour for the table and use of one of the house’s game sets. The club will also provide the counters or chips used for scoring, and you will be expected to settle all bets independent of the club management’s involvement.

In Japan, some Mahjong parlours have automated tables that shuffle the tiles, stack them and form the Wall without human assistance. Many also offer “charms”—food and drink—as part of a Mahjong package.

Mahjong tournaments are becoming popular as a means of advancing and applying one’s skills, too. Most parts of the world have their own organisations that arrange these, such as the British Mah-Jong Association, the China Mahjong Association, and the European Mahjong Association.

The biggest tournament, the World Series of Mahjong, is now held annually at the Wynn Casino in Macau and attracts hundreds of players from all over the world. The cost of entry is $1,000 and the grand prize is half a million dollars. The main event is played by standard WSOM rules, accompanied by a side event held according to Riichi Mahjong rules.

Online Mahjong Clubs also provide an excellent venue for newcomers to learn and practice the game. Most provide free downloads to new members.

And within the Skill Games areas of many Internet casinos, there are often sections for players to meet, form tables, and enjoy wagering or playing for fun. Mahjong Solitaire, Old Style Multiplayer Chinese Mahjong, and Jackpot Mahjong are just a few of the software applications available.

One of the most active online communities for Mahjong players is MahjongTime.com. In association with the North American Mahjong Federation, it provides tutorials, tournaments and the ability to form “guilds” in various styles of the game. These range from Chinese Official Mahjong and Riichi to American, Classical European, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese rules.